From Nonprofits to Narratives – Abril Peña’s Concept of Community & Creativity

- Yamberlie

- Apr 16, 2025

- 12 min read

Abril Peña is a writer, advocate, and community organizer whose life and work are deeply rooted in her Dominican heritage. Nacida y criada en Queens, Nueva York, como la hija mayor de inmigrantes dominicanos, Abril sabe lo que significa vivir entre dos mundos. Abril’s life has been shaped by the complexities of being both a proud Dominicana and an American.

By day, she’s the Corporate and Foundation Partnerships Manager at the Citizens Committee for New York City, helping secure funding for grassroots organizations that make a real difference in local communities.

By night, she’s a writer—her words unapologetically honest, vulnerable, y siempre en busca de la verdad más profunda sobre la identidad, la familia, y la cultura. Whether she’s managing partnerships or writing essays, her genuine desire for building connections and making a real difference in people’s lives comes through.

Microgrants & Big Dreams

In her professional life, Abril wears many hats, but at the core of everything she does is a deep commitment to her community.

Abril’s work in the nonprofit sector no es solo un trabajo—it’s a mission. In her role at the Citizens Committee, she helps secure funding for microgrants aimed at supporting community-based organizations and small businesses in neighborhoods that often go overlooked. “What I love the most is working with corporations to see how we can support each other,” Abril says. “If you say you want to help young people, or support the arts, or environmental projects, how can we do that together? That’s what excites me.”

She works tirelessly to help fund microgrants for community organizations and small businesses in underserved neighborhoods across New York City. “I really do like working with corporate partners to figure out, like, how can we meet the goals that you have?” Abril says with palpable enthusiasm. “You say you want to help young people, or support the arts, or help with environmental projects… ¿Cómo podemos hacerlo juntos? That’s the kind of stuff that I enjoy doing.” It’s clear that Abril thrives on finding creative, practical solutions that align corporate goals with community needs. Para ella, lo más satisfactorio es ver cómo esas conecciones benefician directamente a las personas que más lo necesitan.

While working on securing funding and supporting organizations through partnerships is fulfilling, Abril’s role isn’t without its frustrations. “Grant writing doesn’t really allow for creativity. It’s more like filling out these 20 pages of questions with all these crazy impact expectations,” she admits. “They want to know if I give you two thousand dollars, can you solve world hunger?” She laughs, tempered by her commitment to making things work. A pesar de las frustraciones con la burocracia, Abril sigue siendo enfocada en su trabajo porque se trata de personas reales y cambios reales.

Her work isn’t just about securing money, it’s about creating opportunities for people who deserve them and helping organizations thrive. Her commitment to community is what keeps Abril going and the belief that it’s all worth it if it means she can be a catalyst for something bigger.

“You have to make a case for why this is important. It’s about reminding funders that these communities have been doing the work and just need the resources to continue,” she explains. Es todo sobre crear un espacio donde el talento sea reconocido, las oportunidades sean dadas, y el trabajo real se haga para mejorar la comunidad.

From Healing to Activism

But Abril’s flair doesn’t stop in the office. Outside of her professional work, Abril’s creative side flourishes. Writing has always been personal, her sanctuary even, a place where she can dig into her identity, an outlet that has allowed her to reflect on her own experiences.

In her writing, she explores identity, culture, and the immigrant experience, uncovering themes of struggle, growth, and resistance. She shares her personal struggles, cultural reflections, or perspectives on identity, Abril uses her writing as a tool for empowerment, no solo para ella, sino para otros también. She also sees writing as both an individual and collective act of resistance, casi como una liberación. “Our stories matter,” she says. “I want my writing to encourage others to share their own truths too.”

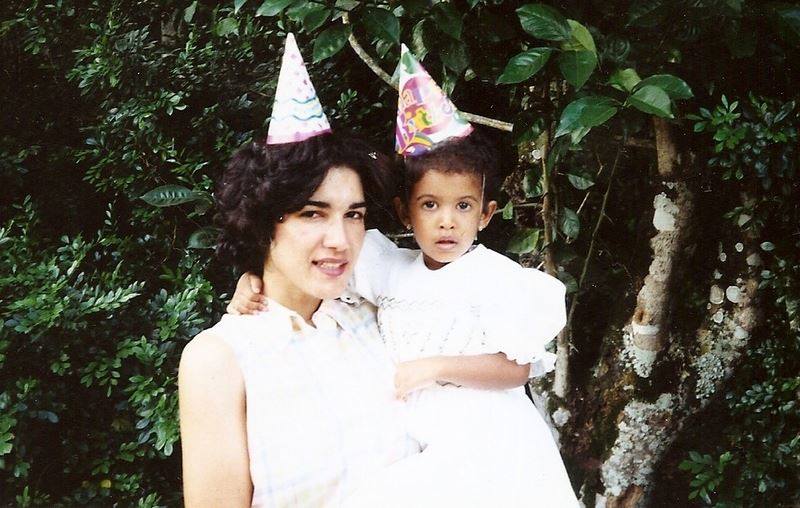

For Abril, writing is also a form of healing. “I always felt like I had to write about my relationship with my mom,” reflexiona. “It was a way of figuring things out, of finding clarity. La escritura siempre ha sido una salida , una vía por la cual puede explorar las complejidades de su identidad. “It’s an extension of who I am, not just a way to get from point A to point B,” she explains.

Sus ensayos han sido publicados en antologías de la Dominican Writers Association, un grupo dedicado a elevar las voces de los escritores dominicanos. La primera pieza publicada de Abril fue más que un milestone en su carrera como escritora—it was a breakthrough in reclaiming her voice. She remembers the catharsis of writing her first published piece. “I had been writing in my journal for years, but when I wrote that essay, it felt like I was finally telling my story out loud.” That moment was pivotal. It was a reclamation of her own voice.

Para Abril, no basta solo con ser escritora; she’s passionate about helping others, particularly fellow Dominicans, find their voices and create opportunities para ellos mismos. As someone who actively participates in la Dominican Writers Association, Abril también organiza retiros de escritura para escritores dominicanos, creando espacios donde pueden conectarse, compartir su trabajo, y construir una comunidad más fuerte. “Those spaces are so necessary. They allow us to write, be in conversation with each other, and build something that lasts,” comparte, señalando lo importante que son estos espacios para construir solidaridad y asegurar más voces que sean escuchadas.

Working with Dominican Writers offers Abril something fundamentally different from her nonprofit job—a sense of comunidad that feels both familiar and freeing. “We get to take more risks,” she says. Collaborating with Angy and Mariela feels natural, like working alongside familia. “I’m heard and seen by them in a different way than when I’m at wire, where my outrageous ideas would never make it past a board meeting!”

The cultural connection is undeniable. In her nonprofit work, Abril often feels like she’s translating her experiences for others. “In my team, I’m the only person of color. In the organization itself, I’m not, but I’m one of few.” That disconnect becomes apparent when she’s advocating for comunidades she resembles more than the colleagues around her. “I tend to reflect more like the people that we’re serving…than say the people that I work with.”

It’s frustrating to push back against microaggressions or bring up concerns, only to be told, “Well, you know, these people are giving us money, so we kind of have to just listen to them.” Working with Dominican Writers is the opposite of that erasure. It’s about conexión and recognition. “We all have a primo or tía or, you know, whoever who is similar to us,” Abril explains. But even that closeness has its own complexities. “You might treat everybody like that’s your tía, your primo…but maybe they want to be treated as a professional writer.” Finding the balance between autenticidad and professionalism is an ongoing challenge, but one Abril embraces.

Lessons from Mami and Papi

La familia es el corazón de todo lo que Abril hace.

Growing up in a close-knit Dominican household, Abril’s parents instilled in her un sentido de orgullo por lo que es y de dónde viene. Their influence has shaped every aspect of who she is, from the way she approaches her career to the values she holds dear.

Her parents’ differing qualities have shaped Abril into someone who values both independence and emotional connection, traits that sometimes clash but often complement each other in her life. “My mom is like a firestorm,” she laughs. “She’s the one who gets things done, who pushes me to always do more. My dad, though, is the one who’s more in tune with the emotional stuff. He’s the one who calls and says, ‘I love you.’ He’s the one who’s always there, even if I don’t realize I need him.” Abril often finds herself reflecting on how both of her parents have contributed to the woman she is today—her mother with her ambition, drive, and independence, and her father with his care, emotional intelligence, and constant support.

“My mom definitely taught me, like, have your own money, have your own career, have your own life, don’t depend on a man for anything,” Abril says, emphasizing the fierce independence her mother instilled in her. Her mother, an architect with a sharp mind and an even sharper focus, embodies the concept of “businesswoman” through and through. “I think I got my drive and ambition from her,” Abril reflects. “She’s a powerhouse—she’s always been the one to push me to go further, to chase what I want in life without relying on anyone else.”

Her mother’s influence is undeniable, especially when it comes to how Abril views her relationship with her partner. “It’s funny because I struggle with my partner sometimes,” Abril admits with a chuckle. “He wants to help me with things, and I’m like, ‘No, I’m good.’” This isn’t because she doesn’t appreciate him; it’s just that her mom’s lessons run deep. “She was always so adamant about being self-sufficient. She never wanted me to depend on anyone, especially not a man,” Abril continues.

While her mother was teaching her to be strong and independent, her father was teaching her the importance of emotional connection and care. “I’ve learned a lot about being emotionally available from him,” she reflects. Abril’s father offers a stark contrast in terms of emotional support and sensitivity. “My dad is such a good man,” Abril says, her voice filled with warmth. “He always pushed me to do things the right way, to be better. He’s been a steady presence in my life, even if he doesn’t always understand what I do.” Despite his reserved nature, her father has always been there for her, quietly cheering her on. “He’s not always sure about my work, but he’s always encouraging me, supporting me in his own way.”

Unlike the traditional image of Dominican men, who may sometimes be seen as stoic or macho, Abril’s father defies those expectations. “He’s not like that at all,” Abril says with a smile. “He’s never been about the machismo thing. He’s the one who’s sensitive, who cares about the little things, and it’s really shaped how I see relationships.”

Her father’s emotional intelligence, paired with his loving support, has influenced Abril’s own approach to vulnerability and emotional openness. “He’s very in tune with his emotions,” Abril explains, noting that her father is the one who calls to check in on her, often just to ask how she’s doing or share a funny story. “He’ll be like, ‘How are you? What’s going on? I heard this funny joke today,’ and it makes me laugh because it’s just so adorable. He brings a sense of lightness that I really appreciate.”

Abril’s family, however, isn’t just made up of her mom and dad. The extended family plays a vital role as well, with relatives who share a deep connection to social justice and community activism. “It seems like nonprofit work is in our blood,” Abril says as she speaks fondly of an aunt who founded a foundation in the Dominican Republic, which plants trees and engages in other community-building efforts. “We just love to make a difference, to change things for the better,” she reflects. It’s clear that Abril’s family carries this sense of social responsibility in everything they do.

Her grandfather, too, left a lasting impression on her worldview. “He was very politically engaged, always advocating for social issues,” Abril recalls. “He wasn’t the traditional Dominican dad who upheld machismo. He was all about education and the well-being of his family.” Abril notes that her grandfather’s progressive mindset—especially his advocacy for education and equality—has influenced her deeply. “I’m lucky because they gave us the opportunity to grow, to become educated before starting a family. I feel like I’ve had the time to build a career and establish myself before having children, which is something not everyone gets.”

As Abril reflects on her upbringing, she also envisions ways to deepen her connection to her parents through writing. “I think it would be amazing if I could write letters with my parents,” she says. “I want to know their innermost thoughts, what makes them tick, what they really think about the world and about life. I think my mom would be an amazing writer if she gave it a try. I’m dying to hear her stories.” Abril remembers how her mother would post long, poetic messages on Facebook, filled with thoughts on politics, music, and social issues. “Any talent I have with writing comes from her,” she says with pride.

She also envisions a project where her parents share their thoughts on paper, a way for her to preserve their voices and experiences. “If I gave them a pen and a piece of paper, I’d love to have a tangible piece of them, something I could keep forever. I want to capture the wisdom they’ve passed down to me, because it’s invaluable.” It’s clear that Abril holds a deep respect and admiration for her parents—not only for the way they’ve shaped her life but also for the wisdom and experiences they carry within them.

Through the years, Abril has come to realize that she’s both a product of her parents’ contrasting yet complementary influences and someone who carries their legacies in her own way.

Como ella misma dice: “Todo lo que soy, todo lo que hago, es por ellos”—everything I am, everything I do, is because of them.

From Page to Stage

Abril’s first moments on stage were a revelation. As soon as she stood at the podium, she instinctively placed her hands on her hips. “I didn’t even notice it,” she laughs. “My boyfriend pointed it out later. He said, ‘You do that when you brush your teeth too.’” Abril chuckles at the observation, but she quickly realized how the stance might look to the audience. “Maybe I shouldn’t be looking at them like a Dominican mother,” she admits. She adjusted, shifted in posture lowering her hands and using them to hold her papers as she read her piece.

“It was all part of the learning process,” Abril reflects. “I want to practice more with body language. Once I get into the habit of reading my pieces, I want to use my body more.” She understands how much of her communication extends beyond the words she writes, how her presence on stage and the way she carries herself can influence the experience. She was determined to improve with every reading, to grow more comfortable and expressive as she navigates this new challenge.

When she submitted her work, Abril had no expectations. To her, hitting submit was an accomplishment in itself. So when she was selected to read, her excitement was tempered by a hint of doubt. Then the flyer arrived—a collection of names and headshots, and there, in the middle of it all, was hers. The only brown face in the lineup. “Oh. Okay,” she thought. She was probably the youngest writer too, and that fact brought both pride and unease.

That night at the WritersRead event, Abril had no idea how much of a transformation it would bring in both how she saw herself as a performer and in how others would see her. She wasn’t just there to share her work, but also to make her mark in a space that often didn’t reflect her experience or her community.

It wasn’t until the night of the event that the weight of it all fully sank in. Abril had invited her parents, her brothers, her partner, and three friends from high school. This would be the first time they saw her perform her writing live. While she’d read at smaller events before, this was different. It felt real.

As she held down tables for her family, her nerves rattled beneath her calm exterior. The audience began to fill in, and she couldn’t help but notice the disparity. They were all white. The only other people of color she could count on one hand. Her family stood out too. It hit her: they were the only ones.

Abril admits. “But then I was just trying to focus on getting through the reading. I was number three, so I was relieved when it was over. But then I started watching the other writers, and I noticed the difference.”

It wasn’t just that she was among a group of much more accomplished writers—many of whom had published books or worked as professors or editors—but the sheer disparity in how her presence was received. During the intermission, one by one, white women approached her. Compliments were given, each one with a kind of surprise.

One woman told her, “I used to teach in the Bronx, and I worked with so many Dominican students. They were so brilliant, but they never had the chance to express themselves like this. It’s so great to see you up there.” It was heartfelt, but the underlying pity left Abril uncomfortable.

Others followed with more praise—“Good job, great job”—but she couldn’t shake the feeling that it wasn’t her words they were applauding. Rather, it felt like her presence alone, the fact that she was there, seemed to hold more weight than her work itself.

The contrast only deepened when it came time for the writers to read their bios. Most of them were seasoned professionals—published authors, editors, university professors. One even had a career as a stand-up comedian. Abril, on the other hand, had a few anthologies to her name, but her résumé paled in comparison.

Still, Abril knows better than anyone that talent isn’t the issue—it’s access. Working with Virtual Enterprises, she had seen it firsthand: students from underprivileged schools given the right tools could excel expectations. The same is true for writers, especially those in spaces like the Dominican Writers Association (DWA). “Hay tanto talento en estas comunidades,” she says. “Pero no se ven como escritores porque no ven a nadie como ellos haciéndolo. That’s why organizations like DWA are so vital.”

When Abril took the stage, her posture and presence were not just about standing tall but about embracing her role as a writer. If the WritersRead event had been her first exposure to the writing world, Abril admits she would have walked away thinking writers didn’t look like her. That she didn’t belong. But she didn’t. Instead, she left with her head held high, knowing her work with DWA was not only important but necessary. As she reflects on the night, she’s fiercely proud of what she’s accomplished.

Comments